When you introduce yourself as a film critic, it's amazing how often the response is: “So what’s the best movie ever made?” As the list on my handy About page demonstrates, I have many favourite movies. In the face of such a question, rather than attempt to explain that no one film is better than all others, I pragmatically pick one of my favourites at random, and cite it as the best film ever made.

In this new ongoing feature, I will highlight all my favourite films, one-by-one. In order of how I’m feeling that day.

First up, it’s the film I’ve probably cited as my actual favourite more than any other: Alan J. Pakula’s The Parallax View from 1974.

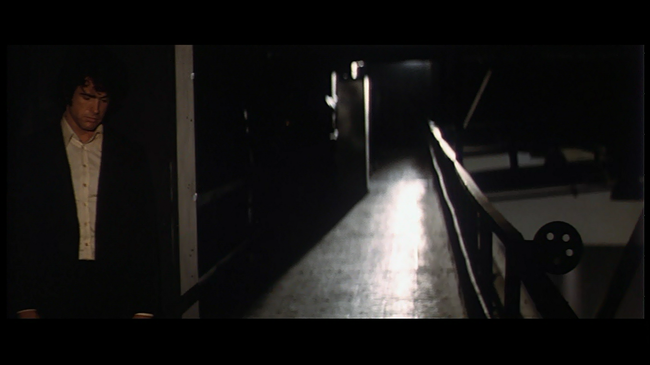

In one of his loosest, most endearing performances, Warren Beatty subverts the action hero archetype as Joe Frady, a muckraking journalist who is present when a rising Senator is assassinated during a press conference atop the Seattle space needle. A literal high bar is set with this bravura opening scene, the climax of which is a chilling, vertigo-inducing action sequence that occurs in total silence (see above).

Years later, Frady dismisses a hysterical ex-girlfriend (the superlatively pulchritudinous Paula Prentiss) when she attempts to warn him that several figures present during the assassination are dying mysteriously. Then SHE turns up dead, so Frady investigates in his unique style, and discovers what appears to be a corporation that recruits sociopaths to be political assassins. Then it gets really interesting.

Pakula takes the film to some startling psychological places, not least during a dazzling sequence (which the film is probably best known for) in which Frady is subjected to a bizarre filmic montage designed to weed out the killer instinct in the viewer:

I had struggled to see beyond Beatty’s reputation as a poon-obsessed lothario before I saw Parallax, but the film turned me into a die-hard fan of the man. The splendidly off-kilter personality he brings to Frady informs every single scene, and he easily holds the film together with his laconic charm.

Frady’s protracted clash with a dim deputy (played by a very young Earl Hindman, aka Home Improvement’s chinless neighbour Wilson) in a small-town saloon constitutes a hilarious deconstruction of a very tired cinematic trope.

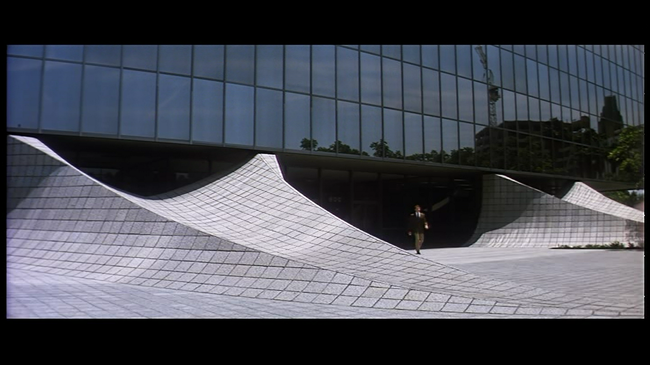

The staging of the various action set-pieces is relentlessly inventive and stylish. They all occur in awkward locations that offer up uniquely ominous overtones. It highlights just how generic most chase/shoot/run sequences can be.

The Parallax View remained a criminally underappreciated classic for many years, overshadowed by Pakula’s other early ’70s works—Klute (1971) and All The President’s Men (1976), both of which are great, but not as great as The Parallax View, which in many ways represents an artful combination of the two other classics.

The film’s reputation has grown in the internet era and now it stands as merely underrated. You’ll sometimes hear contemporary directors citing its visual style as an influence. It’s not difficult to see why this aspect grabs people—the film was shot by legendary DOP Gordon Willis (best known for his influential work in The Godfather), who carves up the screen with recurring grid motifs and shoots all the action scenes in bright, searing light.

The supporting cast is made of some of the best character actors, well, ever: Hume Cronyn; William B. Davies; Kenneth Freaking Mars. Every character encountered, no matter how small, earns distinction.

But what I love most about The Parallax View is how it portrays the insurmountability of what Frady’s up against. Populist film logic dictates that one hero can usually pull out a specific pin and bring any conspiracy tumbling down, but Parallax is all the more chilling for showing just how difficult that would be.

The script was written by David Giler, best known as one of the producers who shepherded the Alien franchise, and Lorenzo Semple Jr, a very successful screenwriter whose legacy will no doubt be defined by his role in the creation of the 1960s Batman show. Beatty’s pal Robert Towne (Shampoo, Chinatown) did uncredited work on the screenplay, as he tended to with all of Beatty’s films during that era. It would be interesting to know which scenes were written specifically for Beatty, considering how well-suited so much of the film is to his singular charms.

I like to think of The Parallax View as the ultimate meeting point between popcorn story-telling and the creative freedom that studio directors were famously afforded in the early ’70s. It’s an auteur thriller with a propulsive plot; an artistic action movie with more than murder on its mind; it’s a head-scratching hum-dinger that gets better with every viewing. And it’s one of my favourite movies.